DNA Data Security Concerns [Survey]

![DNA Data Security Concerns [Survey]](https://images.prismic.io/privacyhq/211f6326-4b5a-43c2-be8e-a2cfe84116f6_dnaheaders.png?auto=compress,format)

In 2018, prosecutors were able to locate the Golden State serial killer by using DNA data to track down a close relative and investigating from thereon. The data was available on an unnamed genealogy website.

Over the last decade or so, DNA testing has become a publicly available service that has been used by millions of people. These services offer special features such as personalized health risk reports, ancestry and family tree research, nutrition guidance, and beauty recommendations.

However, this data can also be used to do other things, like challenge someone’s will or inheritance or predict hereditary diseases by looking at a family tree and available medical information. This could have serious repercussions for such things as paternity/maternity, adoption, and family relationships in general.

We decided to ask over 1,200 people in the U.S. from various demographics for their opinion on how this technology should be used, if at all. From the results, it seems that while the respondents were interested in the service, most of them were uncomfortable with the potential ways in which the data could be used.

Key Findings

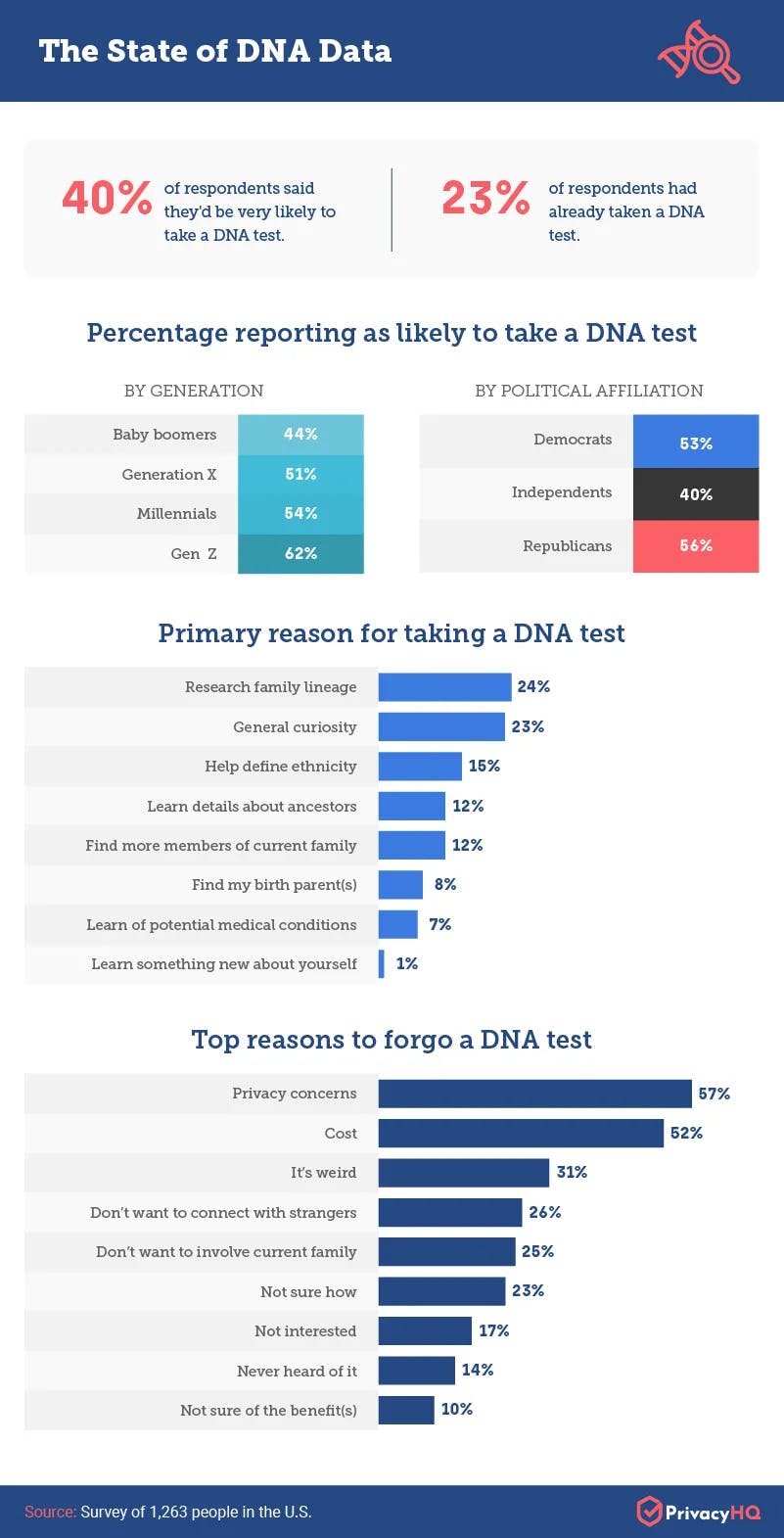

- A large number of people were afraid of their DNA data being shared without consent.

- 57% of people listed concern for privacy as a reason for not getting a DNA test.

- Privacy, not cost, was the top reason for those who chose to forgo the test.

- Education level and political affiliation had an impact on how customers viewed the privacy issue.

- The majority of respondents (79%) felt the government should not have access to DNA data.

DNA Data Sentiments

Just under 300 of our 1,263 respondents had taken some form of DNA test. Out of these, roughly half felt very confident about the accuracy of their results, possibly the results for the other half contradicted known family history or other previously established test results.

The most common reason for getting a DNA test done was to research family lineage, represented by 28% of baby boomers and 35% of Gen Xers. The top reason for Millennials, on the other hand, was simply curiosity (22%).

The most common reason for not taking a test was privacy, followed closely by cost. Politically-speaking, independents were more likely to be concerned with privacy (64%) than Democrats and Republicans (58% and 56%, respectively). Those with a graduate degree were also more likely to be concerned about the privacy of their data.

Is Our DNA Data Secure?

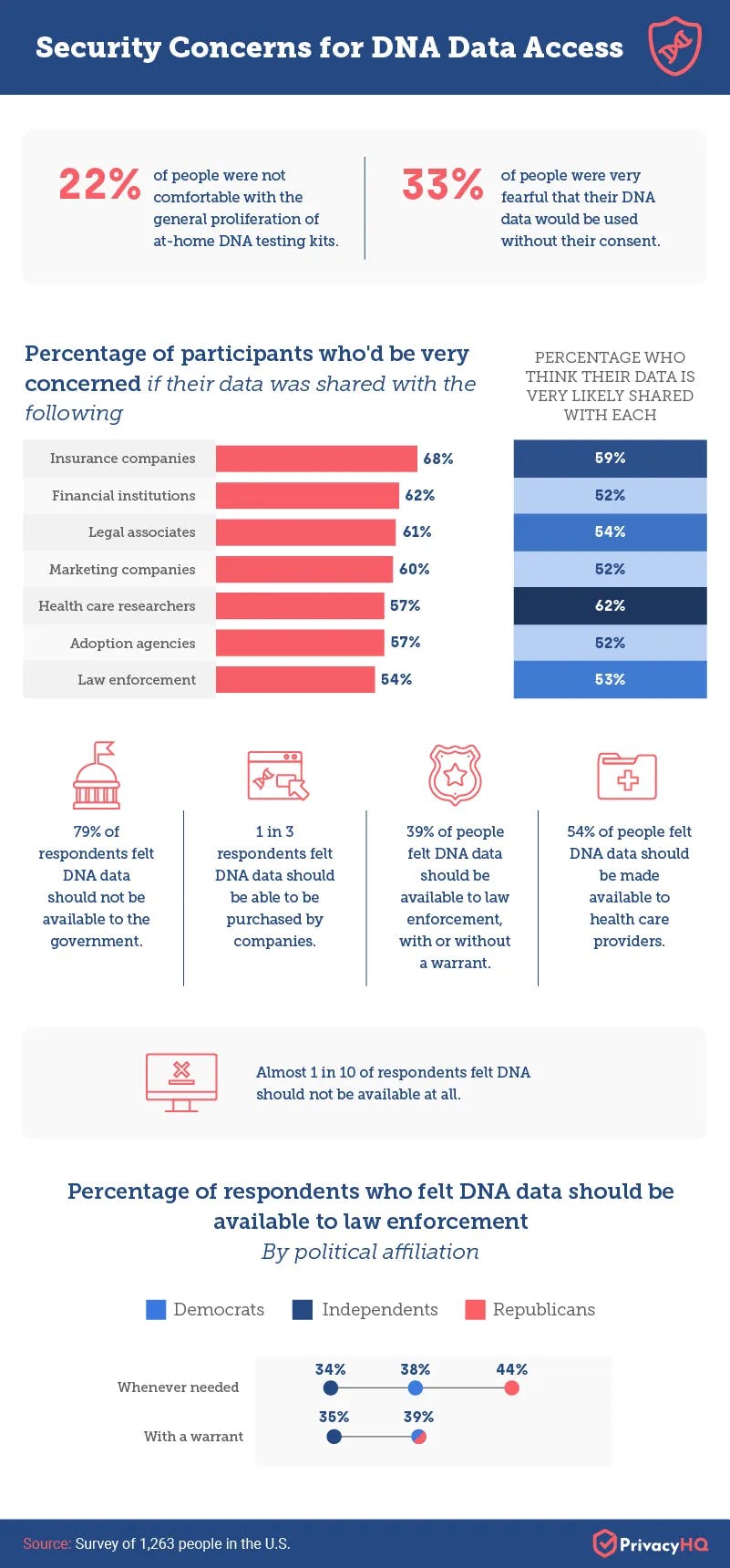

Given the myriad of potential users for DNA data, thoughts about its use are mixed. Data shows that people are least likely to trust the government and most likely to trust health care and law enforcement with their DNA data. Some even felt that companies should be able to purchase their data.

An overwhelming majority of almost 80% of responders felt that DNA data should not be available to the government. Over half felt that the data should be made available to health care providers. Just shy of 40% felt that law enforcement should have access to the data whether they’d procured a warrant or not. About one-third felt that the data should be available for purchase by companies.

Republicans were more likely than Democrats or independents to be OK with law enforcement having warrantless access to their data. Whether they feel this way with full knowledge of the potential of DNA data remains undetermined.

At least 1 in 3 people were concerned that their DNA data will be used without their consent. Some were very concerned about their data potentially ending up with entities like insurance companies, financial institutions, and legal associates. Most of these believed the data is being shared anyway, showing a grim sentiment concerning data security.

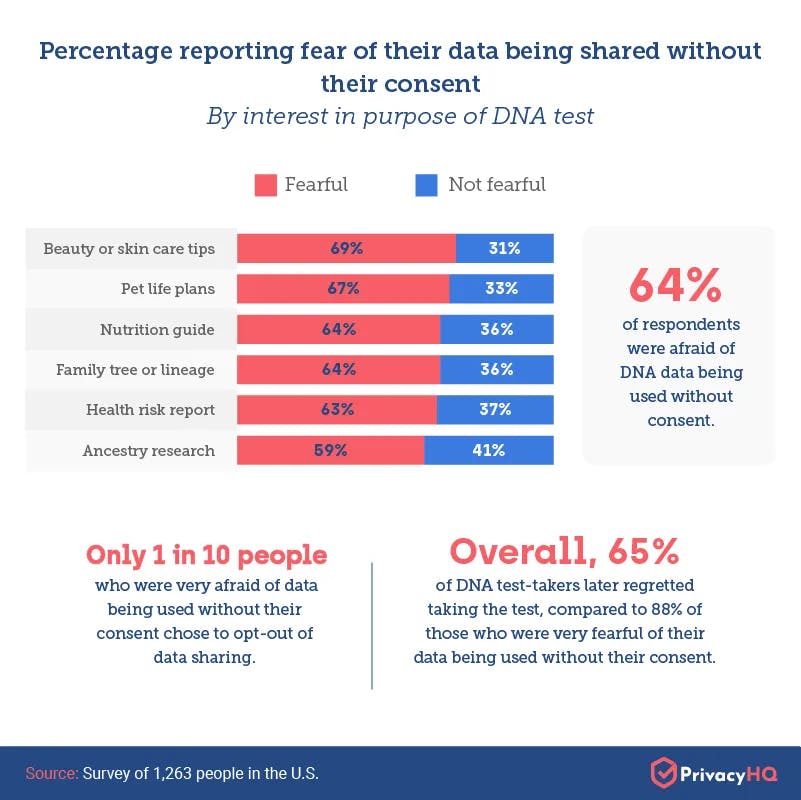

Among those who took the test and were very fearful of their data being used without their consent, only 1 out of 10 chose to not opt-in to data sharing. A strange dissonance that is perhaps linked to the most popular cause for taking the test – researching family lineage.

Ultimately, 65% of test-takers reported regretting it later, and of those reporting being very fearful of their data being used without consent, 88% wound up regretting taking the test.

More than one-fifth expressed discomfort with the easy availability of at-home DNA testing kits. So, it can be inferred that curiosity draws people in, and the true potential for real-world impact dawns on them after the fact, at which point regret sets in.

The Future of DNA Data as We See It

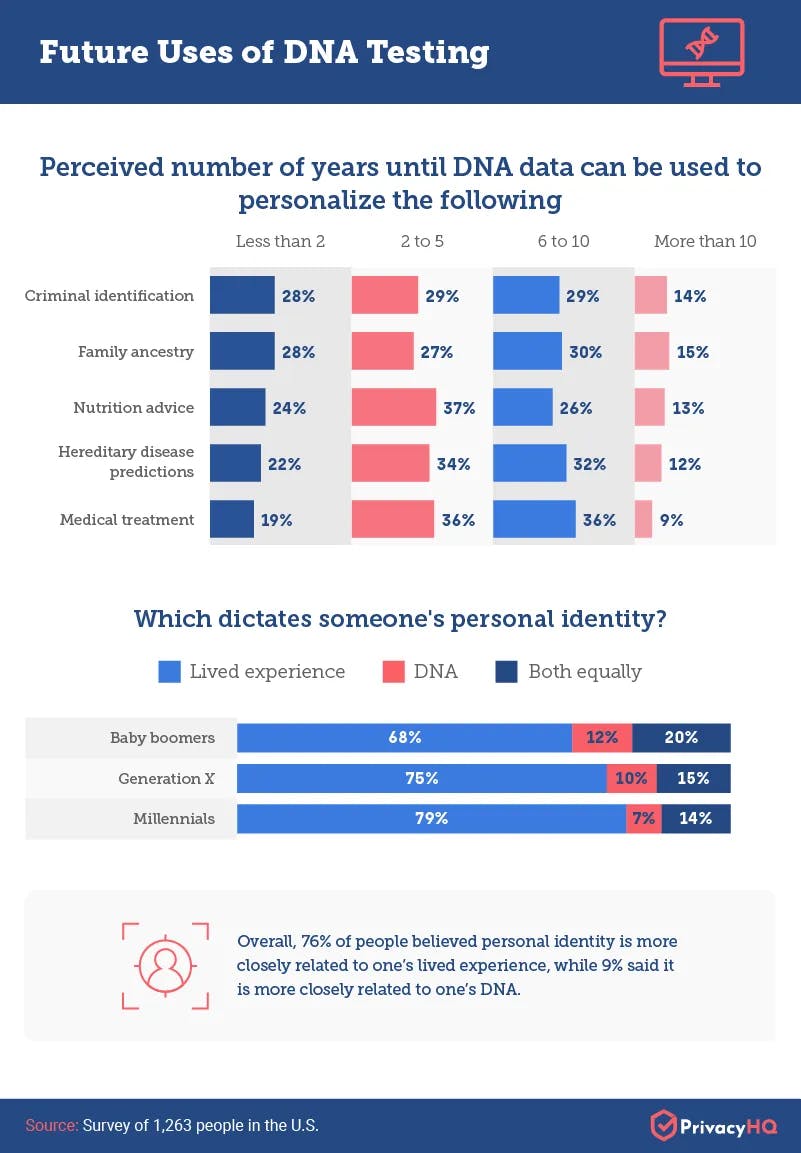

DNA data is already being used in areas such as criminal identification, family ancestry, nutrition advice, hereditary disease predictions, and medical treatment. However, most of the respondents seemed to believe that these uses on a universal level are at least two to ten years away at the moment. This belief perhaps explains why many are willing to part with this most private of information so easily.

Only about one-fifth of respondents believed that all of the presented applications are going to become a reality within two years.

Since DNA data is so closely related to many facets of an individual’s identity, we had to ask how the respondents felt about the nature of personal identity and what it relates to. Overall, 76% believed someone’s identity is related to the unique lived experience of the individual, and only 9% believed it’s more closely related to DNA. It seems that most go with nurture in the nature vs. nurture debate. Interestingly, people who had taken a test were more likely to believe this than those who had not.

Data Privacy

DNA testing is seen with both curiosity and suspicion among contemporary American society. Many want to know about their ancestry, family tree, and the possible diseases they might encounter in life. At the same time, those who understand the high potential for privacy violations through the use of DNA data were also worried about the use of this data without their knowledge or consent. If you want to learn more about data privacy and how to keep your information secure, check out the knowledge base at Privacy HQ.

Methodology and Limitations

We collected 1,263 responses of people living in the United States from Amazon Mechanical Turk, 295 of whom had taken a DNA test. 57% of our participants identified as men, 42% identified as women, and roughly 1% identified as nonbinary or nonconforming. Participants ranged in age from 19 to 84 with a mean of 37 and a standard deviation of 11.3. Those who reported no current employment or who failed an attention-check question were disqualified.

The data we are presenting rely on self-report. There are many issues with self-reported data. These issues include, but are not limited to, the following: selective memory, telescoping, attribution, and exaggeration.

Fair Use Policy

We offer our findings freely and encourage you to share the data with your friends and family, especially those who have taken a DNA test already or are considering doing so. Our only requests are that you link back to this page whenever you choose to share our findings and to please only do so for noncommercial purposes.